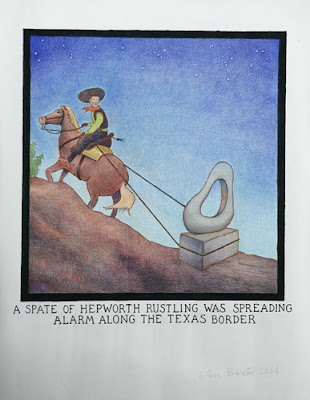

A SPATE OF HEPWORTH RUSTLING WAS SPREADING ALARM ALONG THE TEXAS BORDER.

This was in the Leeds City Art Gallery as part of the ‘Cult Fiction: Art and Comics Exhibition’, September 21st-November 11th, 2007. This touring exhibition featured a selection of graphic novels, sculpture, fine art, illustration and comics. The premise of the show was to examine the relationship between these disciplines. Glen Baxter contributed two pieces to ‘Cult Fiction’, “Looks like you’re slipping inexorably into figuration” 2006 and A spate of Hepworth rustling was spreading alarm along the Texas border, 2006, both placed in the second room of the show (along with their incredibly long titles).

The piece entitled A spate of Hepworth rustling was spreading alarm along the Texas border is set at twilight and shows a pulp fiction style cowboy complete with a bandit’s neck-a-chief, stealing a Barbara Hepworth sculpture. Interestingly both of the art works by Baxter show cowboys juxtaposed with works of fine art as well as concepts from the world of modern art. I find the size of the work remarkable when you consider the media in which the work was created. At 134cm by 108cm, giving just over one square metre, all coloured in pencil crayon, this seems a painstaking approach to image generation at this scale. This adds a certain amount of value to an image which itself is not overtly complex outside of its context of the humour.

Glen Baxter was born in Leeds and studied at Leeds College of Art and Design. He describes his attitude to his work as ‘a deadpan Buster Keaton kind of approach’. This is no more apparent than his representation of a cowboy on a horse, stealing a stone Hepworth sculpture, possibly weighing over a tonne. Although it does not appear to be a direct representation of an actual Hepworth sculpture, its form signifies her abstract organic style. The hole in the sculpture is a strong reference point because Hepworth was the first modern sculptor to use this in her work (e.g. Pierced Form of the early 1930s).

The composition of the image placed above text is very reminiscent of the Farside cartoons by Gary Larson. The newspaper style, one frame comic and punch-line humour attracted my attention in the gallery, but also made me want to investigate the image further, because like Larson after the initial one liner there is normally another subtler joke hidden in a expression or gesture. This is true of Baxter’s work in this case as well, the cowboy checking over his shoulder casts a comically rye squinting gaze for would be pursuers or the rightful owners of the stolen sculpture which is as important as the statement beneath the image. The whole image has particular significance if you think retrospectively about the time it was produced (2006). Baxter is obviously referencing real life ‘rustling’ of a Henry Moore and Elizabeth Frink taken from The Henry Moore Foundation, Perry Green and the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, respectively.

Going back to the obvious juxtaposition of cowboys and a Modernist sculpture, I wonder if this is a metaphor for the relationship between comic book illustration and fine art. Rough course men like cowboys are not unlike how patrons of fine art view the work of comic books, and what better icon of high arts refinery and sophistication than the clean organic forms of Dame Barbara Hepworth. So is one stealing from the other? Are they equal? Is there a dependency of one on the other, but with benefits for both? Is Baxter feeding off Hepworth’s place in the canon, but at the same time raising awareness and introducing new audiences to her work, like a symbiotic parasite? Yes to all of the above and that is why it is so important.

In conclusion, I find Baxter’s work funny and well informed. It’s easily conceivable how Baxter could gather a cult following, I am curious to find out more about him and from this will actively hunt out any shows, books or catalogues which include his work.